About SH"U"N

Background

The global population continues to grow on a daily basis. According to United Nations (UN) estimates, the global population as of 2015 was 7.35 billion, marking a greater-than 2.2-fold increase in global population over the half century since 1965 (UN DESAPD 2015). At the same time, approximately one in nine people, or a total of approximately 800 million individuals worldwide, are suffering from starvation. Two thirds of these individuals are in Asia (FAO et al. 2015). The demand for fisheries resources as a protein source for these individuals has never been greater.Around the world, the fishing industry and, in particular, small-scale fishing in Asia and Africa has undergone modernization over the past several decades, leading to a dramatic increase in hauls (Mathew 2003). With regard to the state of global fisheries resource use in 2013, approximately 60% of resources were fully-exploited, while 10% of resources were under-exploited, and 30% were over-exploited (FAO 2016). What is seriously problematic is the fact that the proportion of over-exploited resources continues to increase.

The UN Conference on Environment and Development held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 (commonly referred to as the “Earth Summit”) saw the adoption of the Rio Declaration, which is aimed at promoting sustainable development, and the associated Agenda 21 action plan. Shortly thereafter, in 1995, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (UN FAO) issued guidelines for sustainable development of the fishery industry in the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries. The UN Millennium Summit held in 2000 at the UN headquarters in New York City saw the adoption of Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to be achieved by the international community by 2015; of the eight goals proposed, the first and seventh aimed to “eradicate extreme poverty and hunger” and “ensure environmental sustainability”, respectively. In the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) established in 2015 on the basis of these MDGs, the second and 14th goals were to “end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture” and to “conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development”, respectively.

To meet the global demand for fisheries products and eradicate poverty and starvation in a sustainable manner, it is important both to appropriately manage the 30% of currently overexploited resources so that they can recover, and to sustainably utilize the remaining 70% of resources. Asian waters serve as a central stage for global fishing, accounting for 84% of the world’s approximately 56 million fishermen, 75% of the world’s 46 million fishing vessels, and 50% of the world’s 81 million ton ocean catch (FAO 2016). Japan, an advanced country that is a major Asian consumer of seafood, shoulders an important international responsibility in realizing sustainable development of the fishery industry in Asia.

Purposes of our project

For many years, the Japan Fisheries Research and Education Agency (FRA) has estimated and announced the populations of various fish species in international waters as well as the waters surrounding Japan (Domestic Resources: Fisheries Agency/Fisheries Research Agency 2016a; International Resources: Fisheries Agency/Fisheries Research Agency 2016b). For more than two decades, these results have been used by the government to establish total allowable catches (TAC) by international fisheries management organizations to develop management rules, and by stakeholders in the fishing industry to develop sustainable fishing practices through mutual cooperation. Today, however, there is growing awareness that sustainable development of the fishing industry cannot be achieved through management by the government and international organizations alone. This requires consumers, who are the end users of fisheries products, to deepen their understanding of the issue and make good choices.Up to this point, the findings of high-public-benefit research conducted by our agency have primarily been used to develop administrative policy. However, we believe that Japan can further expand its contribution to the sustainable development of the fishing industry in Asia by providing information that can be used by consumers in their everyday dietary life. To this end, in addition to the activities of the government and the fishing industry, the SH""U""N project is being launched with the goal of creating a tool for disseminating easy-to-understand scientific information that can be used to support activities aimed at enabling consumers to contribute to the sustainability of resources through their decision-making. The acronym SH""U""N stands for Sustainable, Healthy, “Umai” Nippon Seafood. The goals of the SH""U""N project are to summarize information regarding the level of fisheries resources, the state of fisheries management, and the health and safety of seafood, and to present this information to consumers in an easy-to-understand manner. By getting consumers to refer to this information when buying fisheries products, it is our hope that they will deepen their understanding of and feel more confident about the sustainability of Japanese fisheries products. In addition, by getting consumers to proactively buy endorsed fisheries products, they will be able to support producers that engage in sustainable fishing practices.

In addition, the SH""U""N project will publish an overall summary of evaluations, the evaluation standards used, and information used as a basis for evaluations. By ensuring transparency, the SH""U""N project aims to encourage diverse stakeholders in each region, including fisheries organizations, processing and distribution organizations, certification bodies, consumer organizations, environmental NGOs and educational institutions, to utilize output from the SH""U""N project to further energize next-generation dietary education, sixth-industry, rural, and sustainable fisheries development, and export expansion.

In other words, the main goals of the SH""U""N project are to energize the varied activities of the diverse stakeholders mentioned above, to restore the link between the dining table and the ocean, which is in danger of being lost, in individual households, and to get consumers to think about the sustainable use of fisheries resources. In the future, the goal will be to disseminate information and data obtained through the SH""U""N project to a broader global audience and to encourage use of this information and data by other Asian countries that, like Japan, consume a wide range of “blessings of the sea” harvested by large numbers of fishermen using diverse equipment and methods. It is our sincere hope that these efforts will encourage seafood consumers around the world to think about the sustainability of fisheries resources.

About the “Fisheries System”

When we hear the term “fisheries resources” in everyday conversation, we typically imagine “fish (fish and shellfish)” in oceans, rivers, and lakes. However, this is only one aspect of “fisheries resources.” Actually, even though a vast number of fish exist in nature, that in and of itself does not make them “fisheries resources.” It is only when we as a society recognize their value and create a system for their effective use that “fish” become “fisheries resources.”The resource economist EW Zimmerman (1888-1961) defined resources as being “born through the interaction of nature, man, and culture” (Zimmermann 1933). To protect and sustainably use resources so that they can be passed down to future generations, we must not only protect nature, humankind, and culture, but also strengthen and thicken interactions between the three and ensure that the interaction is harmonious.

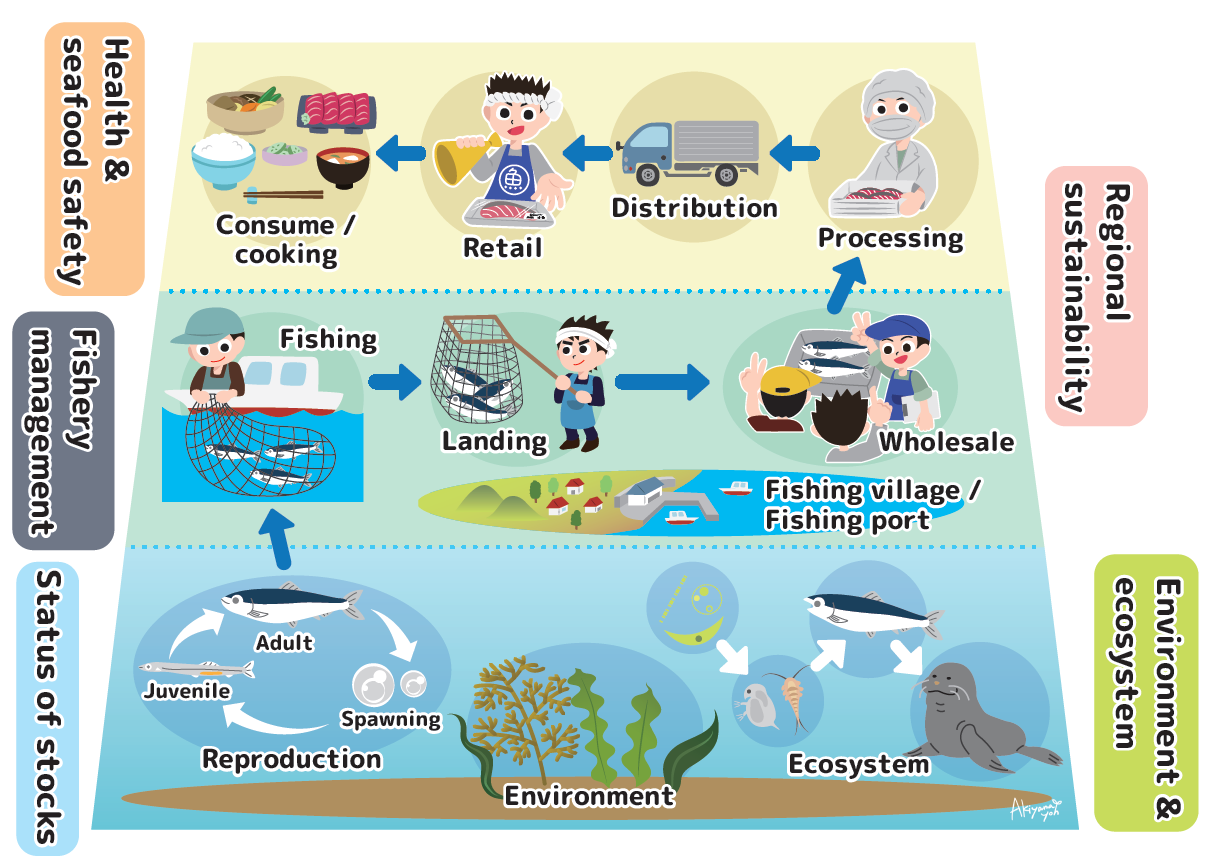

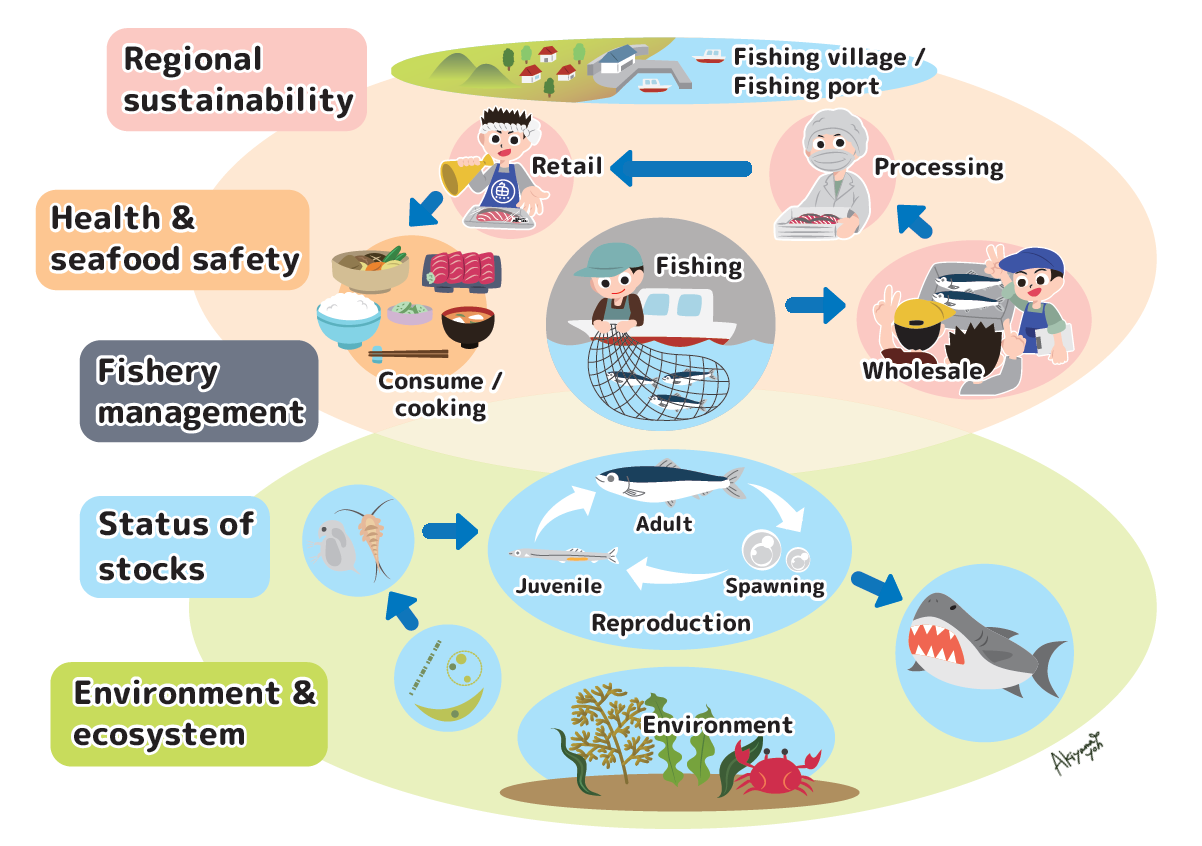

Figure 1 illustrates this way of thinking with regard to fisheries resources based on the results of an investigation into the nature of fisheries resources summarized in The Grand Design of Fisheries and Resources Management in Japan, published by the Fisheries Research Agency (former iteration of the Japan Fisheries Research and Education Agency) in 2009. The figure schematically presents the process starting with the birth and development of fish in the ocean, followed by systematic (to a certain degree) harvest by fisherman in each region, the addition of value via processing and distribution on land, and finally, consumption in individual households. This flow of resources in nature and society is collectively referred to as the “Fisheries System” (FRA 2009). We believe that the way to sustainably use and protect fisheries resources is to strengthen, thicken, and harmonize the entire “Fisheries System.”

Naturally, if there were no fish in the oceans, none could be harvested. Likewise, if there was no fishing or processing/distribution industry, there would be no way to deliver fish to your tables. Furthermore, if our seafood culture were to disappear, fish would lose their value. If any part of the Fisheries System were missing, “fisheries resources” would not exist.

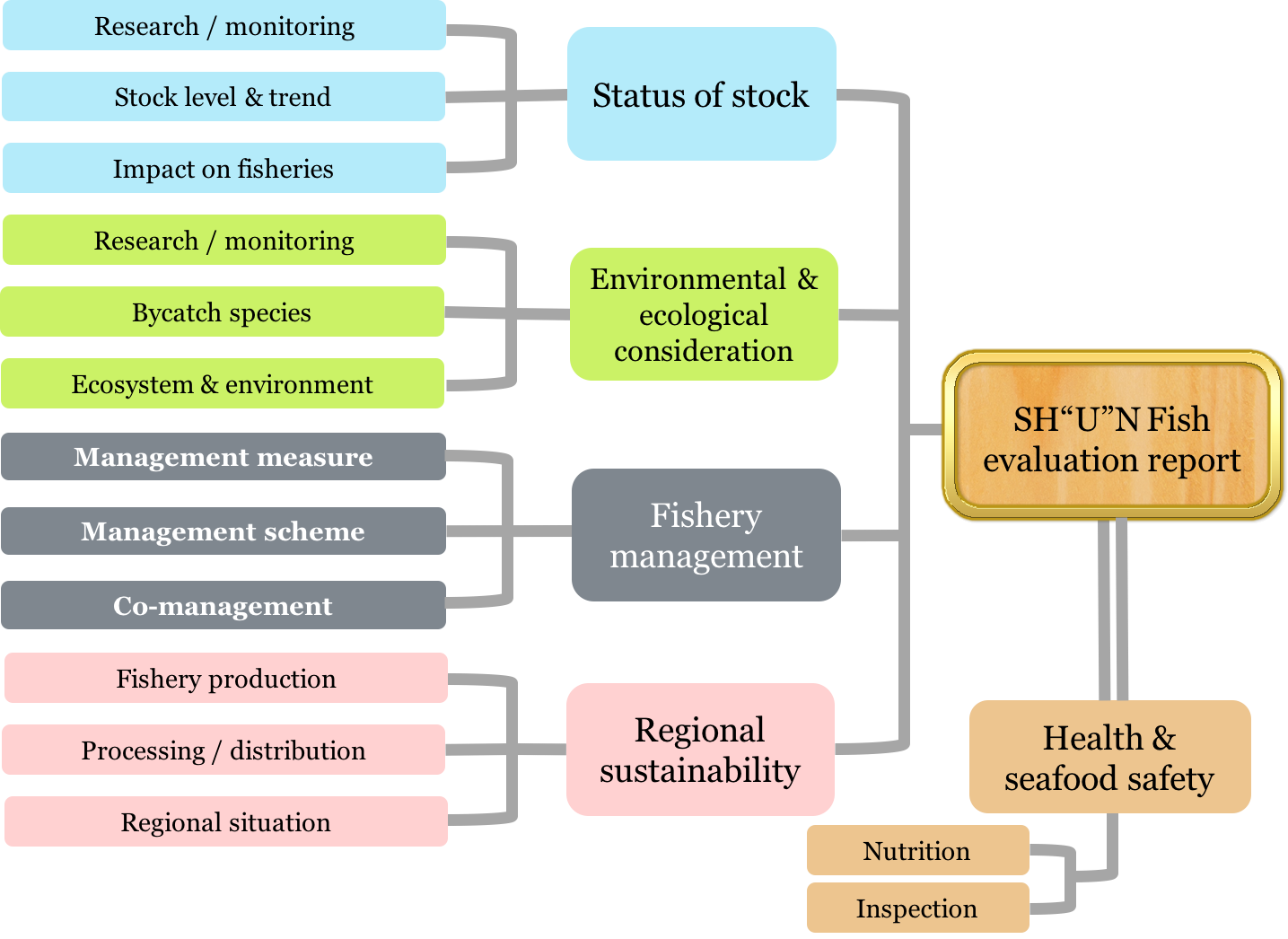

About the criteria of SH“U”N project

To evaluate the entire Fisheries System represented in Figure 1, the SH"U"N project sets the state of resources, care/protection of the ecosystem and environment, fisheries management, and regional sustainability as four evaluation dimensions, and health, safety, and security as an information-provision area (Fig. 2). As our nation’s only institute for conducting comprehensive research on fisheries production, the FRA has accumulated a substantial amount of research results over many years covering these criteria above from diverse fields of study. Based on these research results and all manner of available information, we aim to comprehensively evaluate the sustainability of our nation’s fisheries resources. The reasoning underlying the evaluation methods for each of the five areas is explained below.

Criteria1「Status of stock」 |

||

For more than two decades, resource evaluations conducted by the FRA have been used by the government to set TAC and by international organizations to create fisheries management rules. The first tasks of the SH"U"N project will be to assess whether sufficient research has been conducted on the fish species being evaluated, to estimate populations of these species in oceans, to determine whether these populations are increasing or decreasing, and to evaluate whether transparent and appropriate evaluation systems have been established to enable their sustainable use.

Criteria2「Environmental & ecological consideration」

For fish to be born, grow, spawn, and continue reproducing in the oceans, we must appropriately maintain not only the specific fish species being evaluated, but also the organisms that serve as their food, their habitats, and their relationships with other organisms (Convention on Biological Diversity). For fish in the oceans to obtain sufficient food, correct functioning of the complex food web, starting with primary production by phytoplankton and photosynthetic algae and extending to zooplankton, fish, and fish-eating organisms, as well as various materials cycles, including decomposition of organic matter, is needed. Likewise, appropriate environments, including spawning, nursery, and feeding grounds, must exist in which fish, depending on their developmental stage and season, can form a part of diverse ecosystems through varied interactions with other organisms.Although maintaining well-balanced ecosystems in terms of structure and function leads to sustainable use of individual resources, it is often very difficult to assess whether an ecosystem as a whole is being maintained in a healthy state. To maintain ecosystems, it is necessary to also consider the care and protection of organisms that are not used by people and rare species. The total quantity of organisms that can be sustained (carrying capacity) by a given ecosystem is limited by the size and primary production of that ecosystem. Populations of specific organisms undergo complex changes as a result of interactions with other organisms. As such, it is not possible to increase or decrease the population of a single species without affecting other species. Increasing the population of organisms that are beneficial to people is not the same as maintaining ecosystems in a healthy state overall. Thanks to various research efforts, the structure, functions, and mechanisms of ecosystems, which span multiple species, are gradually being revealed. Examples of such research include the elucidation of synergistic increases or decreases in populations (“species alternation”) of small pelagic fish such as Japanese sardine, Japanese anchovy, and mackerel (Takasuka et al. 2008), analysis of the effect of fishing in the Inland Sea and off the Sanriku coast based on modelling of the food web, including fishing (Watari 2015; Yonezaki et al. 2016), and investigation of changes in the carrying capacity of various environments due to human activity, including fishing, pollution, and land reclamation. Because it would be difficult to evaluate changes in the structure and function of ecosystems in terms of all fish species, the SH"U"N project will evaluate the impact of fishing on other organisms, as well as the ocean ecosystem and environment as a whole, while taking ecosystem structure and function into consideration.

Criteria3「Fishery management」

Japan’s fishing industry is unlike that of advanced Western countries insofar as it has relied on a large number of small fishing vessels that harvest a wide array of resources for domestic consumption using diverse equipment and methods. These characteristics are shared by the fishing industries of other Asian nations (Makino and Matsuda 2011). It is believed that such fishing industries, in general, cannot be effectively managed solely through top-down approaches whereby fishermen are expected to follow rules imposed by the government. Management approaches in which the rights and responsibilities of local fishermen are made clear and the government and fishermen work together to carry out fisheries management have been shown to be more effective (Gutierrez et al. 2011). In recent years, such management approaches, referred to as “fisheries co-management,” have garnered high praise as effective approaches around the world.In Japan, various activities aimed at sustainable resource use have been carried out autonomously by fishermen in different regions since ancient times. The main recommendation of the “Investigative Committee on the Design of Resource Management” established by the Fisheries Agency was to “enhance co-management based on public management by the government and autonomous management by fishermen” (Fisheries Agency 2014). As a seafood-consuming country located in the Asia-Pacific Ocean, Japan has not only an obligation to continue its efforts to enhance co-management based on public management by the government and autonomous management by fishermen, but also an international responsibility to transmit its know-how and experience to neighboring countries. Given these circumstances, it was decided that the SH"U"N project should also evaluate cooperative efforts by regional fishermen and governments to practice co-management as well as the content of such co-management.

Criteria4「Regional sustainability」

Here, we reaffirm the importance of the culture and economy of fishing regions for achieving sustainable fisheries resource use. In recent years, alongside biodiversity, greater emphasis has been placed on cultural diversity around the world, leading to a growing awareness that the accumulation of culture and knowledge generated through the activities of human society is as valuable as biodiversity and should therefore be protected (Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions). In Japan, the fishing industry has provided numerous jobs and supported the economies in so-called disadvantaged areas such as isolated islands and the tips of peninsulas. It is the existence of fishermen and individuals engaged in the processing and distribution of fisheries products throughout Japan that enables such a wide variety of fish to be delivered to the dining tables of consumers. Given the growing severity of depopulation and aging in rural areas in recent years (Masuda 2014), rural revitalization through development of an attractive fisheries products industry has a greater role to play in society than ever.The knowledge and wisdom regarding the ocean that has been accumulated by fishermen in various locations over countless generations has also been widely used in autonomous management by fishermen. The fact that rural communities have continued to exist means that this diverse knowledge, wisdom, and experience has been passed down from generation to generation. The Japanese archipelago, where we have continuously lived and consumed seafood for thousands of years, stretches from north to south and spans a range of ecosystems, from the subarctic waters of Hokkaido to the tropical waters of Yaeyama Island, and have given birth to diverse cultures and traditions that take advantage of the fruits of each region’s ecosystem. In particular, the seafood culture and traditional cuisine in each region are precious cultural heritages that are essential to enjoying the bounty of the sea and that, once lost, can never be recovered. In the SH"U"N project, we believe that ensuring the sustainability of regional societies throughout Japan, which serve as the foundation for preserving and transmitting this diverse culture, is extremely important.

For the future of sustainable resources

About the science outreach of SH“U”N project |

||

In the fourth medium- to long-term that began this fiscal year, the FRA has established four pillars for educational activities: [1. R&D for sustainable fisheries resource use], [2. R&D for healthy development of the fishing industry and stable supply of safe fisheries products], [3. Basic research for ocean and ecosystem monitoring and next-generation fishing industries], and [4. cultivation of human resources to serve in the fisheries products industry]. We do not consider the specific evaluation results for each of the four evaluation dimensions proposed by the SH"U"N project to be set in stone. Rather, the results will be flexibly revised by updating information on resources and ecosystems and incorporating the most recent results of FRA research. It is anticipated that the “enhancement of resource management methods” and “development of resource management methods that take impacts on ocean ecosystems and socioeconomic conditions into consideration” carried out as part of R&D pillar 1 will contribute to more accurate analysis and evaluation of fisheries resources for evaluation dimension 1 “state of resources“ and contribute to a more sophisticated evaluation of ecosystem impacts for evaluation dimension 2 “care/protection of the ecosystem and environment.”

The “R&D related to the safety and security of fisheries products” carried out as part of R&D pillar 2 is directly related to “health, safety, and security.” It is expected that the “enhancement of ocean and ecosystem monitoring and R&D for the collection, preservation, and management of fisheries organisms” carried out as part of R&D pillar 3 will accelerate evaluation and judgment regarding evaluation dimension 1 (“state of resources”) and evaluation dimension 2 (“care/protection of the ecosystem and environment”). Further, to ensure that the project can be carried out smoothly into the future, it is necessary to foster personnel with a broad perspective of fisheries resources and ocean ecosystems. The FRA proactively engages in the development of human resources and has carried out various activities as a research institute whose goal is to connect fisheries resources and consumers. The FRA’s accomplishments in these areas will be reflected in the SH"U"N project.

The connection between “Fisheries System” and our criteria

As explained in the section titled What is the Fisheries Production System?, if any one of the key aspects of Japan’s fisheries production system (resources and ecosystems in the ocean, fishing activities on the ocean, regional society on land, and the health, safety, and security of seafood) is deficient, it will not be possible to ensure the sustainability of fisheries resources. We believe that the five areas investigated by the SH"U"N project, reexamined in the context of the organic relationship between the above aspects, are related as shown in Figure 3.

Freedom fo choice and action based on one's own values |

||

Even assuming compliance to the current legislative system, there are various ways to think about which of the key aspects of the fisheries production system are the most important. It goes without saying that safety and security are important. Up to now, the Japanese fishing industry has experienced various tragedies related to the safety and security of fisheries products, including Minamata disease caused by industrial pollution and radioactive contamination due to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident. We understand that the promise to future generations to never repeat such accidents is a prerequisite that Japan’s fisheries industry must absolutely maintain. With regard to the remaining four evaluation dimensions, the answer to the question of how important each is and how each should be weighted depends on the values of each individual. Some may feel that the state of resources is particularly important, while others may think that the impact on ecosystems is most important.

Still others may prioritize regional sustainability, while some may consider all four dimensions to be equally important. The question of weighting is not one for which science can provide a single “correct” answer. It is a question that each consumer and, ultimately, society must answer through choice. Accordingly, the SH""U""N project will make all scientific information used as rationale for its evaluations of dimensions 1 to 4 available to the public and will not calculate an overall evaluation score but, rather, allow users to freely assign relative weights to each dimension. The goal is to enable each user to adjust the weights according to their own values and way of thinking and to encourage each user to connect the sustainability evaluations based on their own unique way of thinking to purchasing behavior.

It is hoped that the aforementioned information provided by the SH""U""N project will help consumers deepen their understanding regarding the sustainability of fisheries resources and contribute to the realization of a society in which people can consume Japanese fisheries products without worry.